According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the number of passengers travelling by air will double by 2050. This means that the aviation industry's emissions would rise sharply without the corresponding use of SAFs. In order to be able to provide the necessary proportion of SAFs, some of the major oil and natural gas companies loudly announced their commitment to this a few years ago. So what does the reality actually look like?

According to IATA, 80-90% of the required fuel could be provided by SAFs by the middle of the century - other experts are pessimistic about this forecast. BloombergNEF, for example, assumes a share of around 7% by 2050 due to a lack of available feedstock and SAF production facilities.

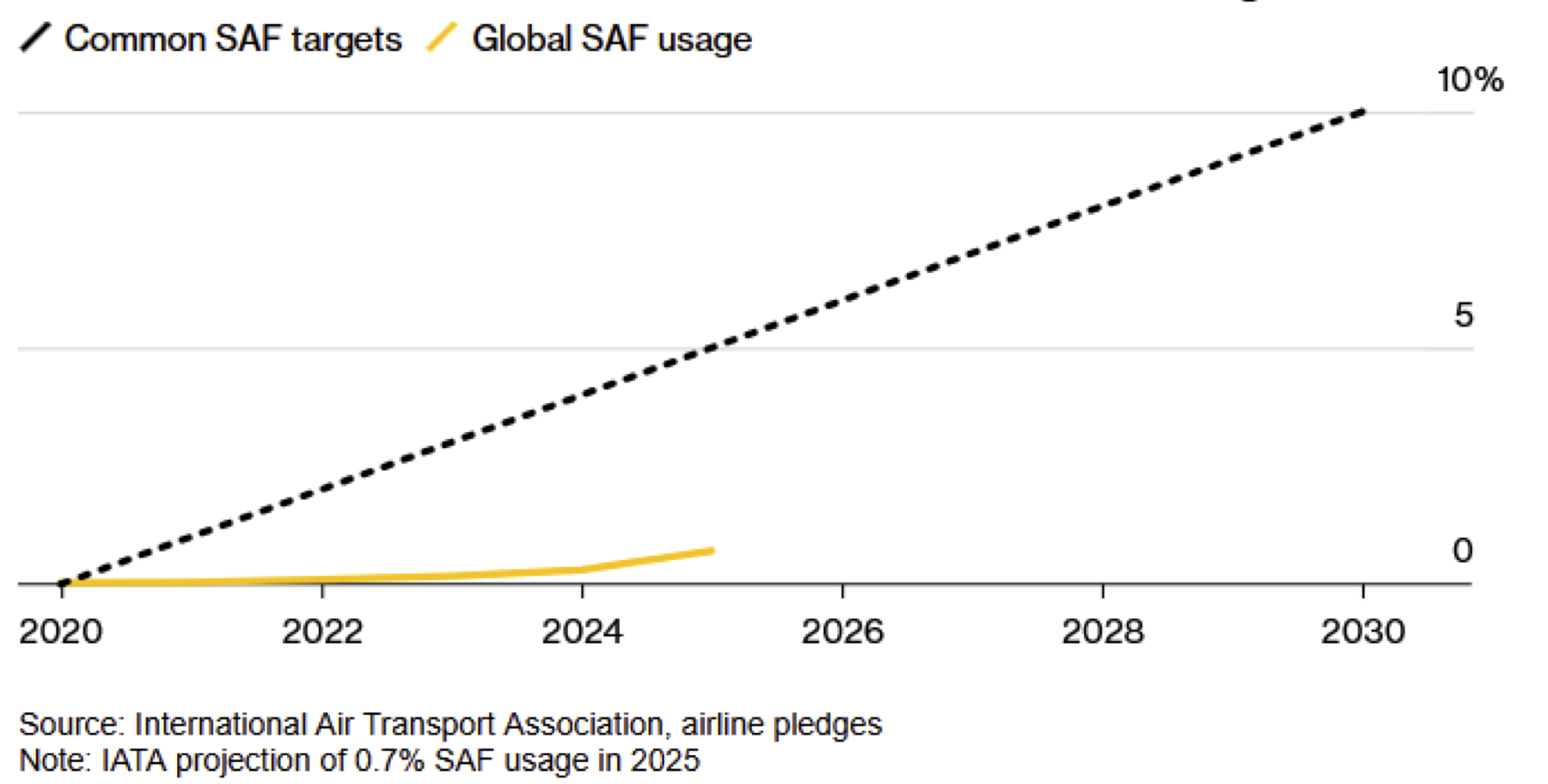

The IATA chart below shows the forecast for the SAF share - based on the airlines' promises in this regard. It can be seen that the actual path to achieving the SAF targets is far from a linear increase - in fact, it has been tiny so far. IATA expects the SAF share to rise to 0.7% this year - up from 0.3% in 2024. However, passenger volumes are expected to increase by 6% from 2024 to 2025 - meaning that CO2eq emissions will rise sharply - almost by leaps and bounds.

In order to increase the proportion of SAFs, some countries, such as the EU member states and the UK, have set lower limits (2% from 2025). Other countries - such as Brazil, Indonesia and Singapore - have also set or are planning to set this minimum percentage. Such rules are intended to protect the pioneers in the use of SAFs from competitive disadvantages - especially as no such obligations are planned in the USA and President Trump has reduced the incentive for the use of SAFs.

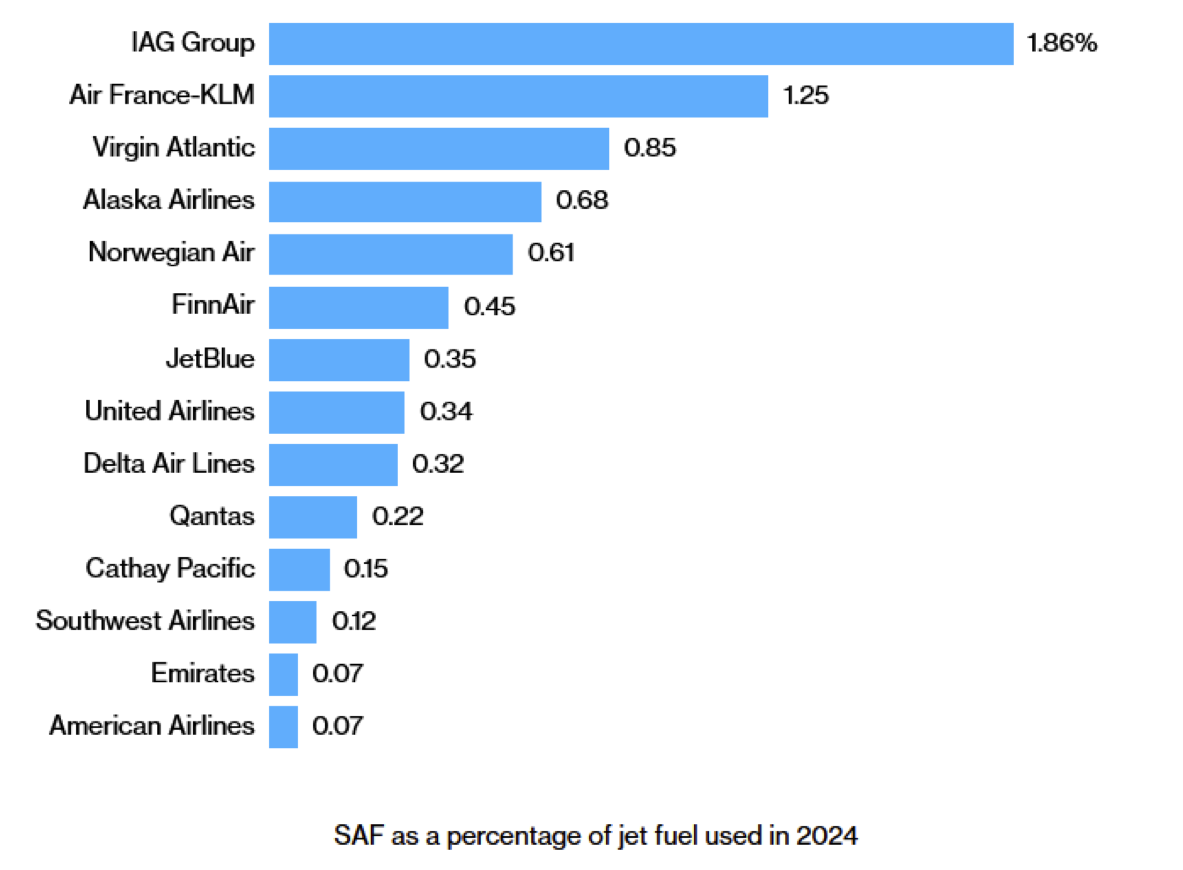

The chart below, taken from Bloomberg, shows the airlines and their SAF share of total kerosene consumption. It can be seen that the European airlines are leading in terms of SAF shares - however, the share is also very low for these airlines.

In order to increase the share of SAFs, which cost twice as much as conventional paraffin, it would be very important for the oil and gas companies to withdraw from SAF production - i.e. to get back into it. For example, BP announced two years ago that it would implement projects that would produce around 50,000 barrels of renewable fuels - with a focus on SAFs - per day. In reality, BP has scaled back these projects and is focussing on fossil fuels again.

In order to get to grips with the challenges posed by rising passenger numbers, ideas are being discussed that go beyond the proportion of SAFs, such as setting fixed emission limits for each airline. This could be achieved, for example, by introducing levies for frequent flyers and/or CO2 taxes.

Good advice is expensive - very often very expensive. Quo vadis aviation industry?